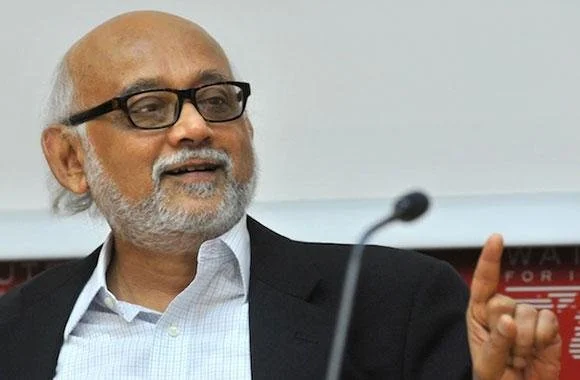

Grain of Sand Award Winner 2022: Partha Chatterjee

Winner: Partha Chatterjee (Columbia University)

Partha Chatterjee begins Nationalist Thought and the Colonial World (1986) with an epigraph from Bertold Brecht’s Galileo: where “there are obstacles the shortest line between two points may well be a crooked line.” This is a fitting metaphor for Chatterjee’s subject of political revolution. It is also an apposite epigram for his creative and sustained engagement with questions of enduring political importance to political science, anthropology and postcolonial studies over half a century of research and teaching on politics, history and political theory. Throughout these decades he has intentionally opened new lines of sight onto the meanings of nationalism, modernity, democracy, history and power: lines that rarely run straight but that invariably have firm destinations at which they deliberately arrive. As he has gone on this journey to energetically and originally interpret political and social worlds, past and present, he has brought along with himself countless other established and emerging scholars as collaborators, students, mentees and inspired readers.

Over his long and prodigious career, Chatterjee has critiqued and upended Eurocentric political and social theory. A founding member of the Subaltern Studies Collective, he has fearlessly questioned sacrosanct ideas and frequently challenged prominent thinkers, including many whose work he admires. In a characteristically acerbic and witty response to Charles Taylor in 1990 (reproduced in Empire and Nation, 2010), he declared his wish to “send the concept of civil society back to where I think it properly belongs—the provincialism of European social philosophy.” He fulfilled this wish by articulating, over some years, what was to become his widely debated theory of political society, most notably in The Politics of the Governed (2004) and Lineages of Political Society (2011), as well as in a variety of other works from among more than two dozen books published in numerous languages; over a dozen edited volumes, and upwards of 150 published articles and essays. Political society for Chatterjee is not a synonym for the free association of civil society, as it was for John Locke, but a site for new and oftentimes uncivil forms of association that emerge with modernity but that deviate from its norms, and seek to be excepted from its order. It is a form of political life that is at once profoundly democratic and characteristically postcolonial; dependent to some extent on the civic and liberal constitutional, but alive in other domains and active on its own terms.

Among Chatterjee’s many talents is an astounding facility for finding and interpreting archival and literary texts, from which he offers historiographic narratives with which to elucidate alternative political and social theories to those of The West. He reads them ethnographically, studies them genealogically, and writes of them evocatively. Marx, Gramsci and Foucault have all influenced his ideas and methods, but his work is not weighed down by theirs. It sparkles with sometimes playful but always meaningful engagement with the writings of contemporaries and predecessors, with reflections on affairs of the present and those of the past. It expresses an abiding need to connect theoretical concepts crookedly with everyday life. This need dates from Partha’s early experiences back in India after completing his PhD at Rochester in 1972. Finding that there was not much call for his training as a game theorist, he joined the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences (CSSS), Calcutta, which he was to go on to direct for a decade (1997-2007). There he learned how to do the inter- and trans-disciplinary interpretive research for which he has become so well regarded. Experiences travelling with colleagues in the countryside of West Bengal, along with those during and immediately after the Emergency (1975- 77), were formative of his intellectual and political positions that took shape in works to come, like The Nation and Its Fragments (1993): a seminal text in subaltern studies and an enduring rejoinder to theories neglectful of nationalism’s polysemy, and inattentive to sovereignty’s multidimensionality.

In more recent years Chatterjee returned to international politics to reconsider the emergence of the modern state through liberal theorizing that animated European colonialism, culminating in his conceptual history, The Black Hole of Empire (2012). Sovereignty also has remained a subject on which he has continued to be heard and read extensively, most recently in I Am The People (2020), from his 2018 Ruth Benedict Lectures at Columbia, and in The Truths and Lies of Nationalism, as Narrated by Charvak (2021), in which, through the voice of an ancient skeptic, he offers an alternative vocabulary for imagining Indian political community. It is all but impossible to discuss Indian politics academically today without referring to Chatterjee's last two books; their impact has been significant not only on US and European academic debates but also on ongoing discussions of authoritarianism, precarity, and contentious politics in much of the global South. That Charvak is already being translated into multiple Indian languages also stands as a testament to how Chatterjee’s thinking continues to attract a lot of interest in India outside of its academy. This is no accident. He has across his career addressed general audiences in magazines and through frequent public talks and lectures around the world. In this way he has remained engaged with current affairs, ensuring that his theorizing stays relevant and constantly subjected to the play of new ideas, and to the possibility of further revision and improvement.

Erudite in conversation, gentle in manner, Partha leaves interlocutors and audiences with lasting memories of a phenomenal capacity to recall prodigious details of research he has done and works that he has read, and to draw crooked lines between events and people that do not even begin to occur to others. He has throughout his life been a generous interlocutor with new generations of scholars, serving on more than 70 dissertation committees in political science, anthropology, history and South Asian or Middle East Studies—at Columbia, the CSSS and other institutions in the US and across the world. His commitment to scholarly engagement with peers, students and mentees is evidenced by the fact that he worked and taught every year but one, between the US and India, over the duration of his career up to retirement. His former students recall his sharply stimulating and punctual comments on thesis chapter drafts, his encouragement of autonomous inquiry and independent thought, and his ability to reinvigorate interest and enliven ideas when they were struggling. In the words of one,

“In order to learn something one must recognize that someone knows something you don’t know. In his 40 years across two academies Partha has trained students in what he knows, and he knows a great number of things. But there is a more fundamental academy to which we belong, teachers and students, in which we are all equal. This is the academy of curiosity. To be taught and mentored by Partha Chatterjee is to be recognized as a fellow traveler in the democracy of the curious, in which he acts as a guide with a light along the way.”

As a fellow traveller in this radically democratic equality of the curious Chatterjee has also been a firm advocate for academic freedom. He has stood in defence of the university as a place protected from the demands of nationalistic politics or patriotic duty. This advocacy is in tune with his widely acknowledged personal ethics and academic integrity. If the academy is sometimes a hostile and competitive place, Chatterjee has demonstrated to his students and peers that empathy and care for oneself and others are integral to scholarly excellence, and hallmarks of the best interpretivist political science. For all these reasons, and more, his contributions merit our special recognition, and gratitude.