Grain of Sand Award Winner 2024: William H. Sewell

William H. Sewell, Jr., the Frank P. Hixon Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus of History and Political Science at the University of Chicago, is the 2024 Grain of Sand Award Winner from the Interpretive Methodologies and Methods Related Group of the American Political Science Association.

The award honors a political scientist whose contributions to the interpretive study of the political has been longstanding and merits special recognition. Originally trained as a labor historian specializing in the period leading up to the French revolution, Sewell’s work has had wide impact on how scholars understand contentious politics, the history of ideas, the role of culture in historical change, the origins of capitalism, and social theory. In doing so, his work has had major impacts in multiple disciplines, including history, sociology, and political science. Consequently, few scholars in the discipline are as deserving of this recognition as Sewell.

Sewell’s first book, Work and Revolution in France: The Language of Labor from the Old Regime to 1848 (Cambridge UP 1980), is emblematic of Sewell’s influence across multiple disciplines. A foundational work in history’s “cultural turn,” the book showed the impact of changing ideas of liberty on the unfolding collapse of the ancien régime through the French Revolution and on to the insurrections of 1848. It challenged the claim that ideas and cultural practices were epiphenomenal to how and why revolutions take place. Early revolutions, Sewell observed, directly inspired later revolutions through the ideas and meaning-making practices that they propagated.

This concern with meaning-making practices and ideas would continue to shape Sewell’s work over the next four decades. In a later book, Rhetoric of Bourgeois Revolution: The Abbé Sieyes and "What Is the Third Estate? (Duke UP, 1994), Sewell showed the importance of rhetoric in creating new political possibilities. Revolutions are not merely the outcomes of material frustrations, Sewell showed; they are also exercises in imagination. Participants need to feel the possibility of change before they can enact it. Rhetoric is one of the ways change is made to feel possible. Yet, the Abbé Sieyes' rhetoric, and the vision it outlined, was filled with contradictions. These contradictions, Sewell argued, were reproduced in the revolutionary project itself, ultimately precipitating its collapse.

Sewell has carefully tracked how ideas and meaning-making practices are co-implicated with material, organizational, and social changes. In Capitalism and the Emergence of Civic Equality in Eighteenth-Century France (Chicago UP, 2021), Sewell documented how new notions of civic equality that helped fuel the French revolution were connected to profound changes in the structure of the French economy and society. As commercial capitalism became the organizing principle for economic life in 18th century France, it had the unintended effect of introducing a new form of commercial equality that made previously unimaginable ideas of civic equality thinkable in the otherwise profoundly hierarchical French society. Tracking this unfolding process over a myriad of different sites, Sewell demonstrated how emerging capitalism radically transformed the structure of society and the possibility for political agency that French subjects could imagine. This process ultimately allowed them to imagine themselves as citizens.

This concern with the relationship between structure and agency, and how scholars should study it, has been a hallmark of Sewell’s profoundly influential methodological work. Published across a variety of journals and collected in Logics of History: Social Theory and Social Transformation (University of Chicago Press, 2005), Sewell’s methodological writings have shown careful attention to the relationship between social structures, the agency of actors to change those structures, and the power of events to shift both. Where Sewell’s work on labor, revolution, culture, and ideas changed how an interdisciplinary group of scholars understand contentious politics, his work on structure and agency have changed how the disciplines understand unfolding historical processes and how to study them. In all these regards, Sewell’s work has itself been revolutionary.

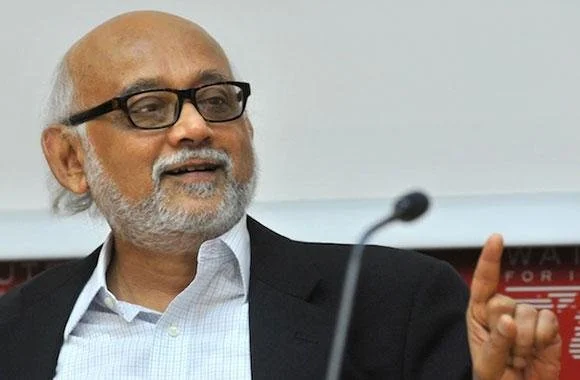

Grain of Sand Award Winner 2023: Timothy Mitchell

On behalf of the Interpretive Methods and Methodologies Section, I am proud to announce this year’s winner, Professor Timothy Mitchell of Columbia University. Mitchell is the William B. Ransford Professor of Middle Eastern, South Asian, and African Studies. As a trail blazer in the fields of political science and postcolonial theory, Mitchell’s widely cited research has explored the place of colonialism in the making of modernity, the material and technical politics of the Middle East, and the role of economics and other forms of expert knowledge in the management and disciplining of collective life.

As one may also learn from his website: Mitchell was educated at Queens’ College, Cambridge, where he received a first-class honors degree in History. He completed his PhD in Politics and Near Eastern Studies at Princeton University in 1984. He joined Columbia University in 2008 after teaching for twenty-five years 2 at New York University, where he served as Director of the Center for Near Eastern Studies. At Columbia he offers courses on the history and politics of the Middle East, colonialism, and the politics of technical things.

Mitchell is the author of the pathbreaking book Colonising Egypt (University of California Press, 1991), in which he charted the emergence of modern modes of governance in Egypt’s colonial period. An influential theoretical investigation into the forms of truth, reason, power, and knowledge that helped make modernity what it is, the book was also a methodological tour de force. Inspired in part by a Foucauldian approach to discourse analysis, Mitchell examined the felicitous conditions under which colonialism’s specific “will to power” gained traction— and the kinds of work it accomplished refashioning subjects and reproducing the rule of Europeans abroad. The book was simultaneously an imaginative and sophisticated foray into the theory and methods associated with Bourdieu and with Derridean deconstruction. Mitchell’s insights into the peculiar ways in which the colonial encounter required that colonized populations be put on display—made visible, exoticized, and sanitized for western consumption—opened vistas for fruitful new research and attunements in the study of both politics and history.

Grain of Sand Award Winner 2022: Partha Chatterjee

Partha Chatterjee begins Nationalist Thought and the Colonial World (1986) with an epigraph from Bertold Brecht’s Galileo: where “there are obstacles the shortest line between two points may well be a crooked line.” This is a fitting metaphor for Chatterjee’s subject of political revolution.

Grain of Sand Award Winner 2021: Mary Fainsod Katzenstein

Through her extensive research, mentorship, and teaching, Dr. Mary Fainsod Katzenstein has intentionally and imaginatively explored issues including (but not limited to) ethnic politics, social movements, feminism, and mass incarceration. By epitomizing how political scientists may elucidate and critically challenge enduring political questions and concepts for and with many communities, Mary’s work is exemplary within the interpretivist community.

Grain of Sand Award Winner 2020: Hanna Fenichel Pitkin

From The Concept of Representation (1967) to The Attack of the Blob (1998), Hanna Pitkin’s work has elucidated the multiple meanings of concepts and the implications ordinary language use analysis holds for revealing how we think and act in the world. Inspired in large part by the writings of Ludwig Wittgenstein and Hannah Arendt, Pitkin’s fine-grained analyses of terms such as representation, justice, judgment, and membership have operated, as the sand metaphor suggests, as an irritant within the academy, perturbing conventional modes of thinking— challenging us all to unsettle existing assumptions, as she did, and to view our tacit knowledge critically.

Grain of Sand Award Winner 2018: Lee Ann Fujii

Dr. Lee Ann Fujii passed away unexpectedly in March 2018, and if she would cringe at anything, it would be an award citation that begins with a long and detailed summary of her (vast) research accomplishments. As a gifted presenter who helped so many of us craft talks and manuscripts, Lee Ann always encouraged us to “Start with a good story!” and “Get people interested!” Taking her advice, this citation begins with a number of stories, because it is impossible to choose only one about someone as vibrant and brilliant as Lee Ann.

Grain of Sand Award Winners 2017: Peregrine Schwartz-Shea and Dvora Yanow

There can be no more deserving winners of the Grain of Sand Award than Peri Schwartz-Shea and Dvora Yanow. Everything they have done and accomplished fits the spirit of the award. Through broad, sustained, and no doubt lonely effort over the last fifteen years, they have worked to build a vibrant, eclectic, and self-sustaining community of interpretive scholars.

Grain of Sand Award Winner 2016: Mary Hawkesworth

Some time in the early 1990s, in discussing the possible creation of a journal in what was coming to be called interpretive policy analysis, one of that field’s leading scholars observed about Mary Hawkesworth’s 1988 Theoretical Issues in Policy Analysis, that her having written it meant that the rest of us didn’t have to.

Grain of Sand Award Winner 2014: Deborah A. Stone

As a scholar and as a human being, Deborah Stone is a model of how to make a difference in the world. She's a leading constructivist theorist who is deeply involved in the practical world of policy design and implementation and manages to build bridges of understanding across these too-separate worlds.

Grain of Sand Award Winner 2013: James C. Scott

Ever since his book The Moral Economy of the Peasant: Rebellion and Subsistence in Southeast Asia (1976), Jim Scott has demonstrated how the meaning-making of the people in the settings one studies is central to political understanding and analysis. Drawing on years of field research in Southeast Asia, Scott brought fine-grained attention to ethnographic detail into conversation with high level theory to produce sophisticated and persuasive accounts of the centrality of contextualized meaning-making to the operation of power.

Grain of Sand Award Winner 2011: Anne Norton

Anne Norton is an ideal honoree both for her scholarship and for the work she has done in the profession to expand the scope of what counts as knowing in political science. Her research record exemplifies her tireless efforts to change how political science is done and what types of political science are valued. Her 95 Theses on Politics, Culture & Method (Yale University Press, 2004) provides a stunning assault on political science orthodoxy and opens multiple possibilities for using interpretive and antifoundational approaches to understand power, politics, culture, and identity.

Grain of Sand Award Winner 2010: Bud Duvall

Bud Duvall. Brilliant, impressive, important scholar. He made a mid-career change from being a cutting-edge quantifier/modeler to (for lack of a better term) a post-positivist orientation. He has long, long, long struggled to make an important space for critical, non-positivist, qualitative work against considerable odds at Minnesota, where he created and sustained the "Minnesota School" of scholars – an invisible college of his students that includes Tarak Barkawi (Cambridge, UK), Michael Barnett (Minnesota), Roxanne Doty (Arizona State), Mark Laffey (LSE), Himadeep Muppidi, Jutta Weldes (Bristol, UK), and Alex Wendt (OSU).

Grain of Sand Award Winner 2009: Lloyd I. Rudolph and Susanne Hoeber Rudolph

We are honored that Lloyd Rudolph and Susanne Rudolph have accepted the Grain of Sand award for 2010, the first one to be given. In the view of members of the award committee, they embody the attributes described above both personally and in terms of their work.